Outer Space presents:

Gather

by Erin Elyse Burns

March 4, 2018

Discovery Park

“Gather took place on a walking path loop in Discovery Park on March 4th, 2018, a date that marks the one year anniversary of my mother’s death. To engage with the simultaneously isolating and community driven experience of loss and grief, I walked a 4.5 mile loop within the park and laid out a single stretch of black ribbon the entire length of the path.

This ribbon calls to mind varied mourning practices seeded in the Victorian Era, references family lineage and life lines, and charts the physical distance of the path as a way to demarcate the meditative and clarifying effect walking has on the mind and body. This is contrasted against the physical toil of gathering and carrying the weight of the ribbon.

The performance began with me walking the route on one end of the loop, gathering the ribbon alone. On the opposite end of the loop path, a group of invited community members walked together, attached by the riboon, collaboratively gathering as they slowly progressed. At a chance mid-point along the path, we met, and I gave the group my bulk of ribbon to carry – alleviated of its mass and weight. We reconvened under a large leaf maple tree once we completed the loop path and staged the sculptural object of ribbon for the public to view during a post-performance reception. ”

— Erin Elyse Burns

INTERVIEW AND DOCUMENTATION:

After Gather was performed, I sat down to have a conversation with Erin to hear her ideas and reflections on the piece in more detail. The transcript of the interview below is an edited and heavily abridged version of our conversation. To read the full text click here.

FKP: Let’s start with the background of Gather – how it came to be, what you were thinking of when you were developing it, the backstory to it.

EEB: Distance, walking, endurance, and performative gesture – often for the camera as witness – have been a part of my practice for a long time, so I’m compelled to think about physical activity – and in particular, toil – as a mindset from which to make art. Site-specificity, landscape, and location-based content are also frequent aspects of my work. Performative intervention in public space is something I’ve been working with since I moved to Seattle 10 years ago. Discovery Park as a site holds a lot of meaning for me personally, and has a rich and complex history. Marrying my different interests with the desire to create a single stretch of black satin ribbon, five miles long, that would run the course of a favorite walking path is also an extension of work I was making back in graduate school at UW’s School of Art Photomedia program. This project was a leap in terms of its scope – it was a big piece.

EEB (cont’d): Gather came in response to my mother’s illness and her eventual death. Around that time – a year ago – I was walking in the park daily as a way to process loss and grief. Regardless of what’s going on in my life, I walk in the park weekly – I live nearby. And the walking path I used is meaningful to me because of its rigor, its variability, its beauty, and that it is a loop. I have a hard time doing there and back walks. The loop enlivens me. I was really interested in activating that route, sharing it with others – releasing it as “mine.” Particularly during bereavement, I began thinking about using that loop as a way to connect to ideas of the lifeline, family lineage, the circle of life, the cyclic nature of everything. Tapping into those interests of distance, physicality and then choosing to use the ribbon as a way to demarcate these ideas is how the work began. I also thought about the piece for about eight months before the actual making began… marinating on ideas is a big part of my process.

FKP: How did Gather being in public, rather than being in a controlled environment, affect the experience?

EEB: I’m interested in the concept of private things happening in public, and to activate both of those spaces simultaneously. We tend to think that public activity leads to a public persona, but then there are these interesting moments where you see something really private happen in public and it shatters social, cultural expectations.

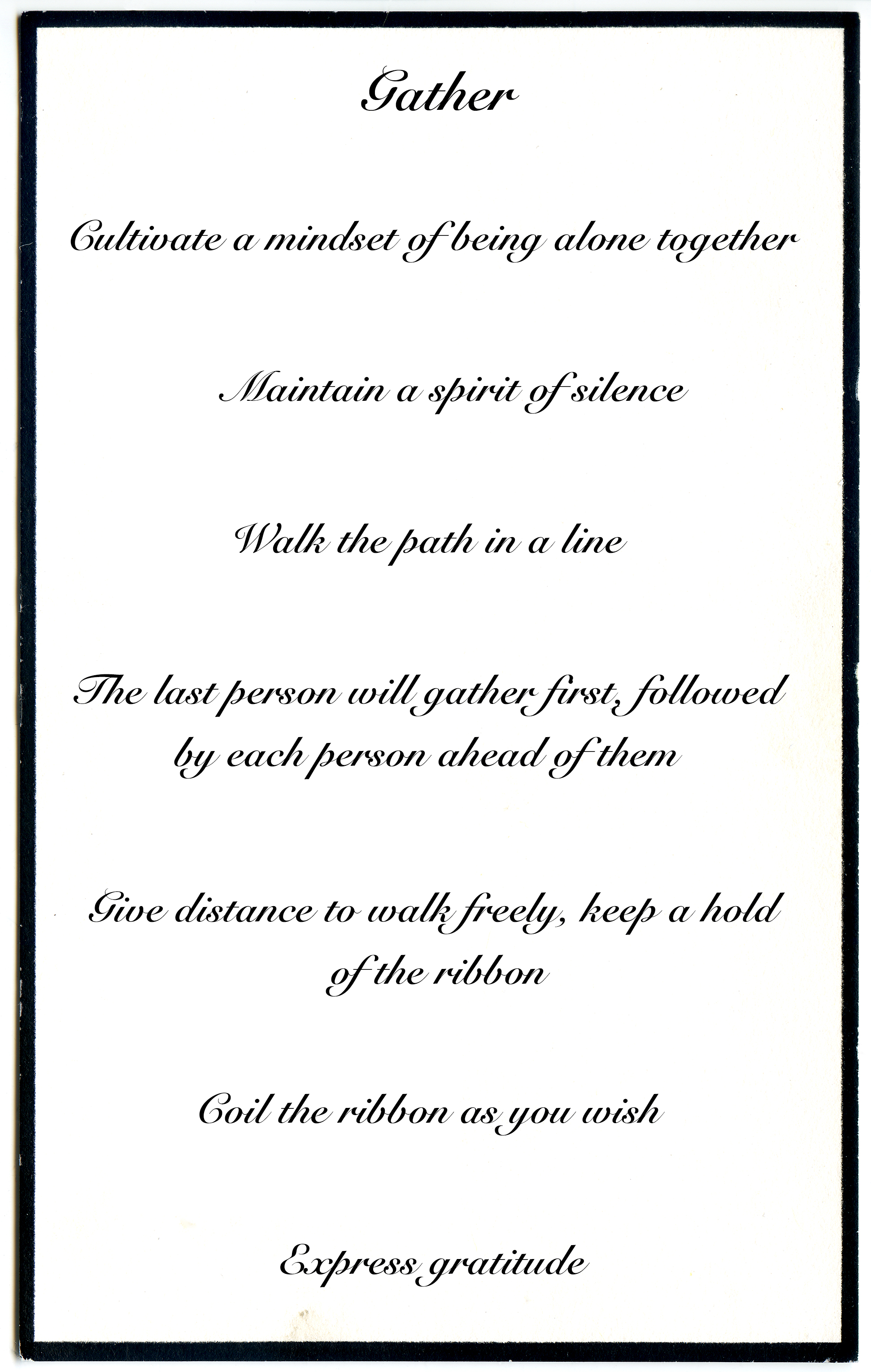

To do this silent performance and to have many people encountering me – expecting me to talk – and to respond in silence, then dig through my ribbon to give them a performance decorum card was really interesting. It taps into a bigger part of the work’s content. How do we communicate without words? Without explanation people are forced to think based on what they’ve observed is happening and come to their own conclusions, and I’m excited by that charge.

EEB (cont’d): A lot of people acted as though they weren’t looking at me, which immediately made me think about what happens when we’re confronted with difference. What happens when we’re confronted with something we don’t understand? What happens when we see something we don’t want to see and can’t process it – how do we deal with that? A lot of times people turn away. There were a lot of sociological observations that you could look at, from people really wanting answers from me, to people being very observant and respectful, to being perplexed, to having dog meetups and not noticing me trying to pass, heavily encumbered…

A lot of the people I encountered had seen the ribbon for some time, walking its length, which seemed to feed their curiosity, and then when they encountered me they had an experience. There were a lot of wonderful observations from kids like “LOOK IT’S WHERE THE RIBBON COMES FROM!” There was a little girl who was just freaking out by the amount of ribbon. Her mom had to sort of talk her down – she was jumping and pointing. “Ok, she’s gonna keep moving,” and then the girl screamed, “BUT LOOK AT HOW MUCH RIBBON IT IS.” That was delightful. Another child said something like “Oh, sometimes people follow string so they won’t get lost,” to her dad. These were really beautiful freed observations that got to the heart of the piece with that childlike whimsy that can be hard for our adult brains to access.

-

(photo by Winnie Westergard)

FKP: Could you talk about what the silence in the piece meant to you?

EEB: I practice silent meditation and have done a few silent meditation retreats, so I’m interested in the kind of knowing that can happen with a community when you don’t speak – the kind of learning and intimacy you can develop sitting near someone you’ve never exchanged words with, but say, you know the soles of their feet intimately.

There’s something that’s captivating about knowing through that kind of experience and not through verbal explanation. That was a big influence in asking a large group of people to gather the ribbon together, to be able to figure out how to do it without talking, to be able to figure out what someone needs in front of you or behind you, or what you need without having to say it. How can we be attuned to those impulses responsively, as opposed to having to say, “Tell me what to do, can I help you?”

EEB (cont’d): I see that kind of intuitive support as having a correlation to what a grieving person, to what I experienced and needed during grief. I didn’t feel able to explain to people what I needed, but I needed them to know. A lot of people typically ask “What can I do? How can I help you?” And it can feel like they are saying, “Tell me what to do. Help me help you.” That is a very natural and human response, but it’s also in opposition to being helpful because then, you, bottomed out and at your weakest, are tasked with a role you can’t fulfill, which I found impossible when in profound grief. The idea of intuitive communication and intuitive support came from thinking that we all can benefit from developing better skills to observe what someone needs without having to be told. And, at times, learning that there is no help we can provide that is greater than the help a person can provide themselves.It’s so hard for us to witness weakness, to show up, to be present, to help beyond words…

(video by Forrest Perrine)

EEB (con’td): In having a relationship to silent meditation, when you’re not talking, your thoughts have the potential to get really loud, so you have this opportunity to observe the kind of thoughts you have. Some of the people in the participants group are meditators and most are not. I was really interested in this idea of having a group that through participating in this piece would be confronted with their thoughts in some way. A lot of the participants I’ve talked with have acknowledged that was an important part of their experiences.

EEB: The latter. I had been making the project On Borrowed Time, which looks at mourning stationery and text – phrases that people either said to me during grieving, the medical process, or language that got stuck in my head after Mom died. So I had been working on this project that was a direct response to my mom’s death, but abstracted through words and the stationery to create distance there. I’ve spent time researching and reading about Victorian mourning practices, which I’ve been interested in for a while, and looked to the idea of sympathy stationery and that black line, which is harder to find in contemporary stationery now. It used to be a common practice to have dedicated mourning envelopes and stationery as a part of the social etiquette of loss.

That was captivating to me as a way to respond to some of the difficulty of contemporary grieving. A lot of people often said to me, “I don’t know what to say,” “I don’t know what to do.” It’s challenging to come up with an immediate answer for grief-related decorum or etiquette, especially those of us who aren’t part of a religious faith. I was interested in looking to a time when there was more of a set list. I spent time thinking about those traditions and that was a direct influence to the work. I wanted to lift the black line off of the stationery and imagine what that black line would look like in space. The black line is also related to the tradition, which is less common now too, of wearing a black band around your arm when someone dies.

There are many walking artist forebears and performance artists that I’m continually inspired by – looking at Richard Long, Francis Alÿs, Janine Antoni, Ernesto Pujol and other interdisciplinary artists that use their body in various ways. Those sources are always influential to me. Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust, which is history of walking, is a must read, and pretty much everything I’m interested in she’s written a book about.

(video by Sierra Stinson)

FKP: Last question: how’s the recovery process been? That was pretty wild, I know you went to the spa the next day, but how are your mind and body doing after this?

EEB: Physically, my body is healing from the strain of the piece. That’s something I need to be mindful of because I do these endurance works and then if I have injuries afterwards I think, “Oh, you should be gentler. How do you be gentler?” I continually engage with the work of being gentle with myself, and this piece is a helpful step in that process. My mind feels clear and I’m enjoying the spring season so far!

Thank you, Forrest, for the occasion of this interview, and for your support of Gather. It has meant the world.

FKP: Thank you Erin, I loved it!

*Huge thank you to Winnie Westergard, Gina Dominguez, and Sierra Stinson for their contributions to the documentation of Gather and to Sue Elvrum for her editorial assistance.